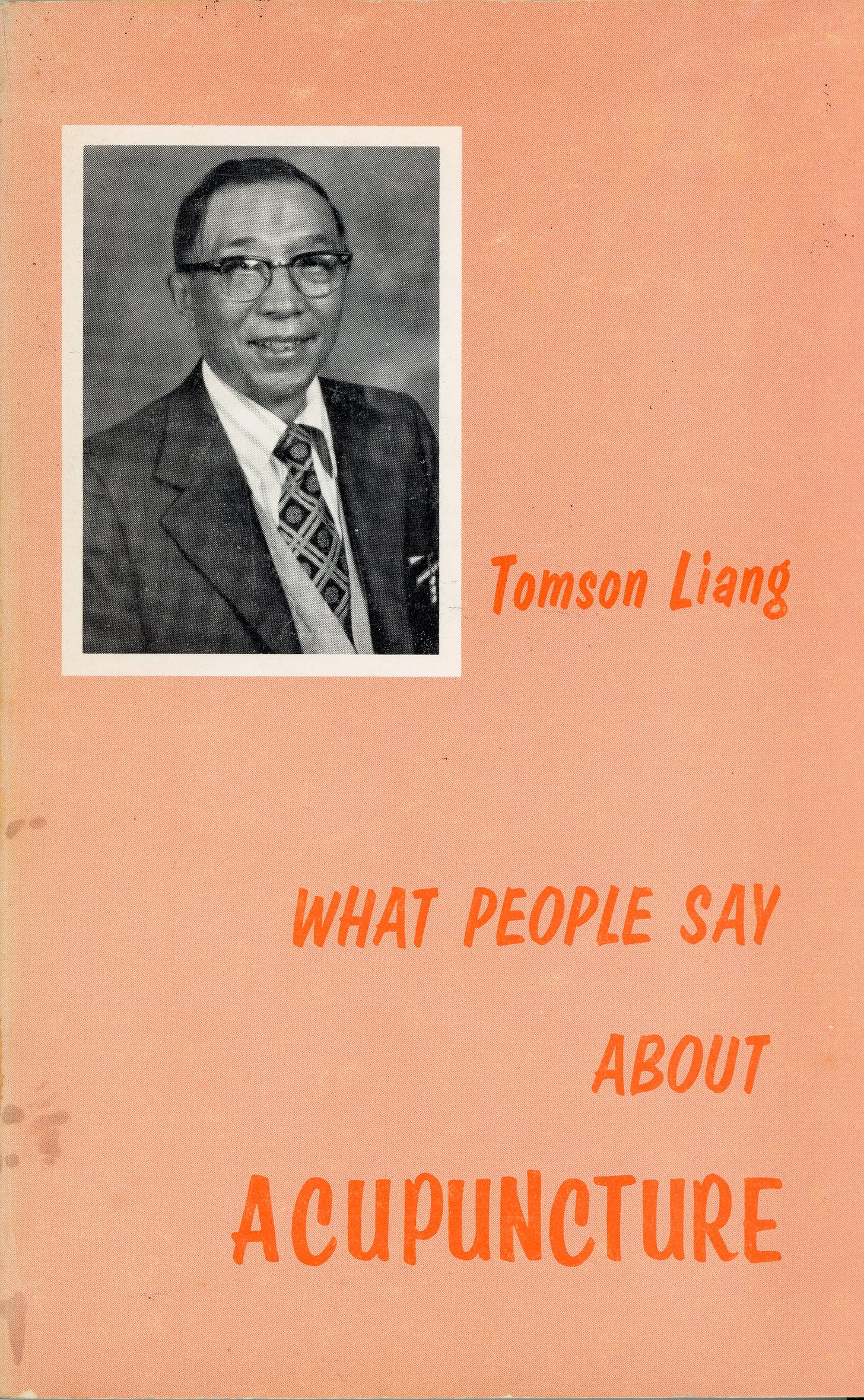

Last year my friend and mentor Russell Brown aka Poke Acupuncture came over to my apartment to listen to some acupuncture cassettes I had recently found. Russell stumbled upon this book, What People Say About Acupuncture by Tomson Liang.

Today I am sharing his word’s accompanied with scans from the book about an important part of Acupuncture’s history here in the United States.

From Russell Brown:

Who wants to learn a little American Acupuncture history today??

No one! But let's do it anyway.

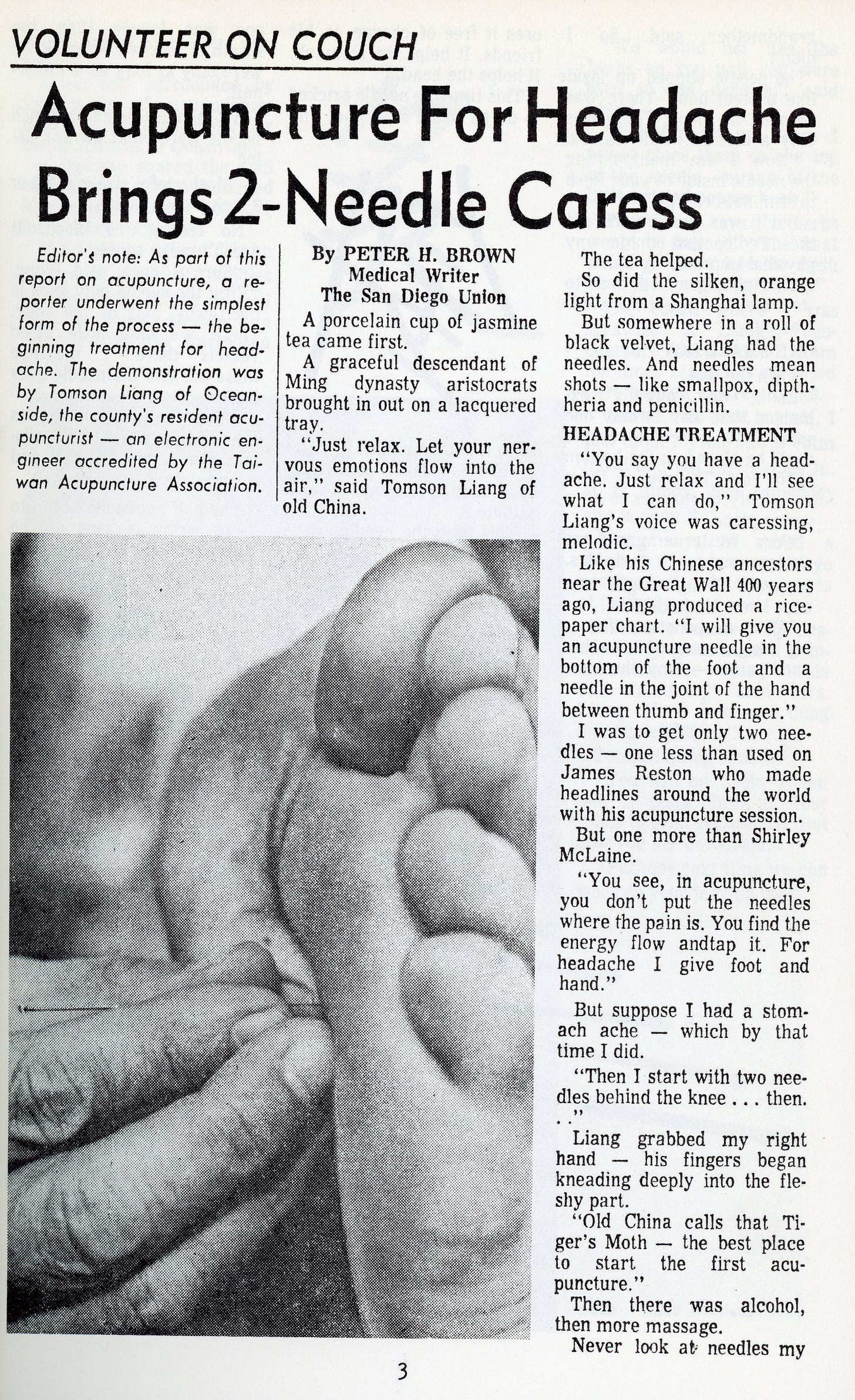

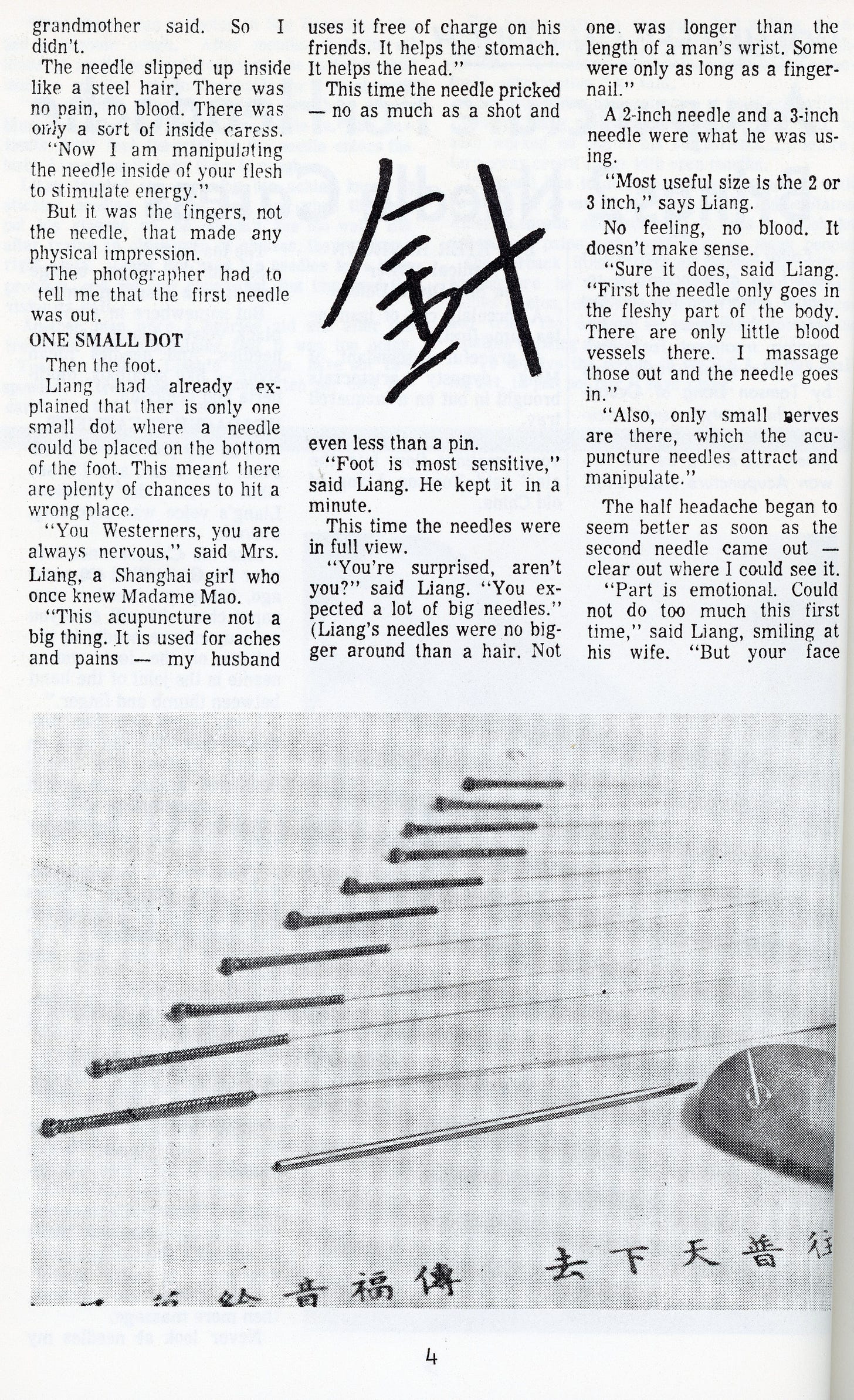

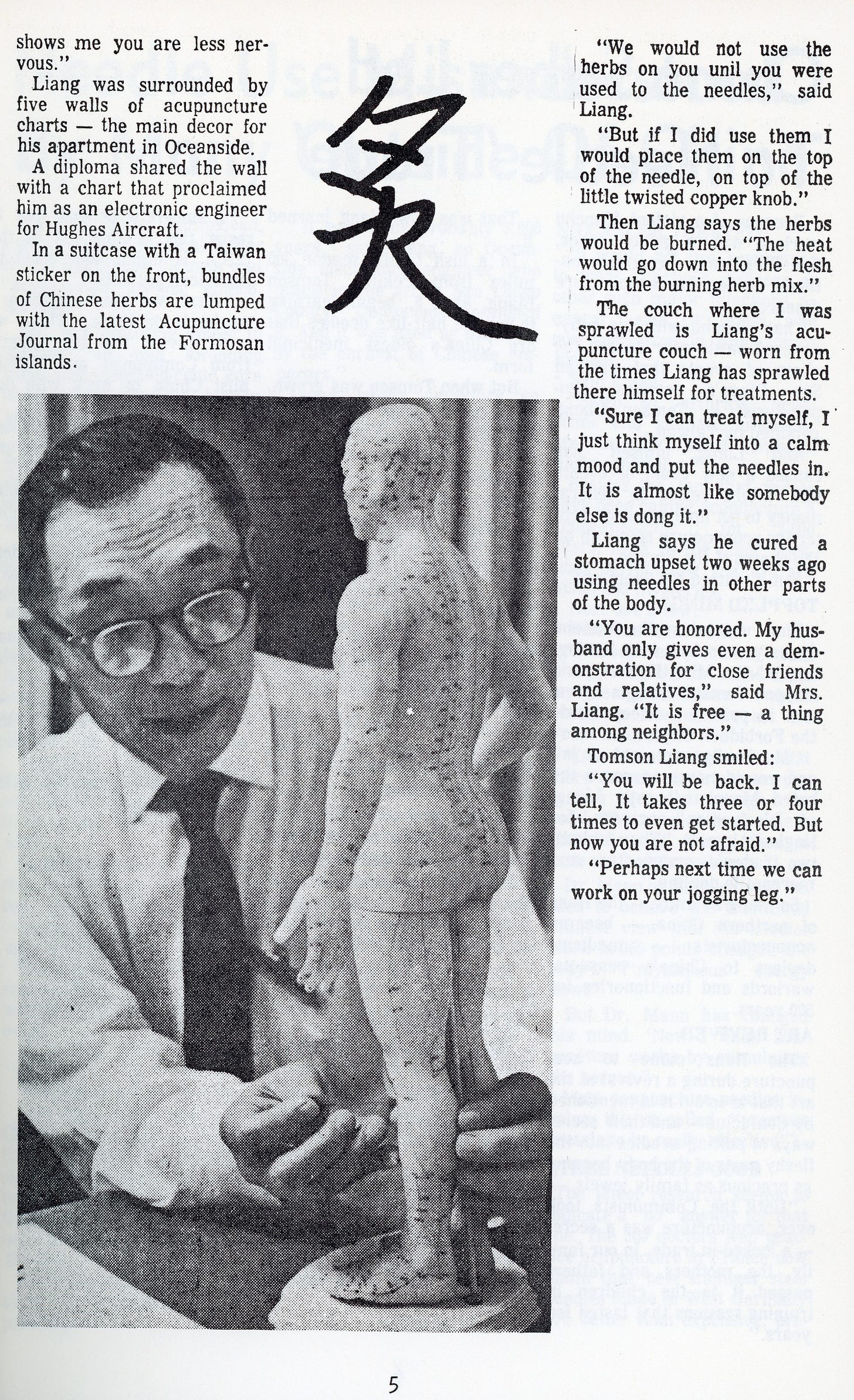

Today's ACUPUNCTURE HISTORY MEGA POST comes from Dr. Tomson Liang's book "What People Say About Acupuncture" (1976)– one of the most important historical texts in the story of American acupuncture.

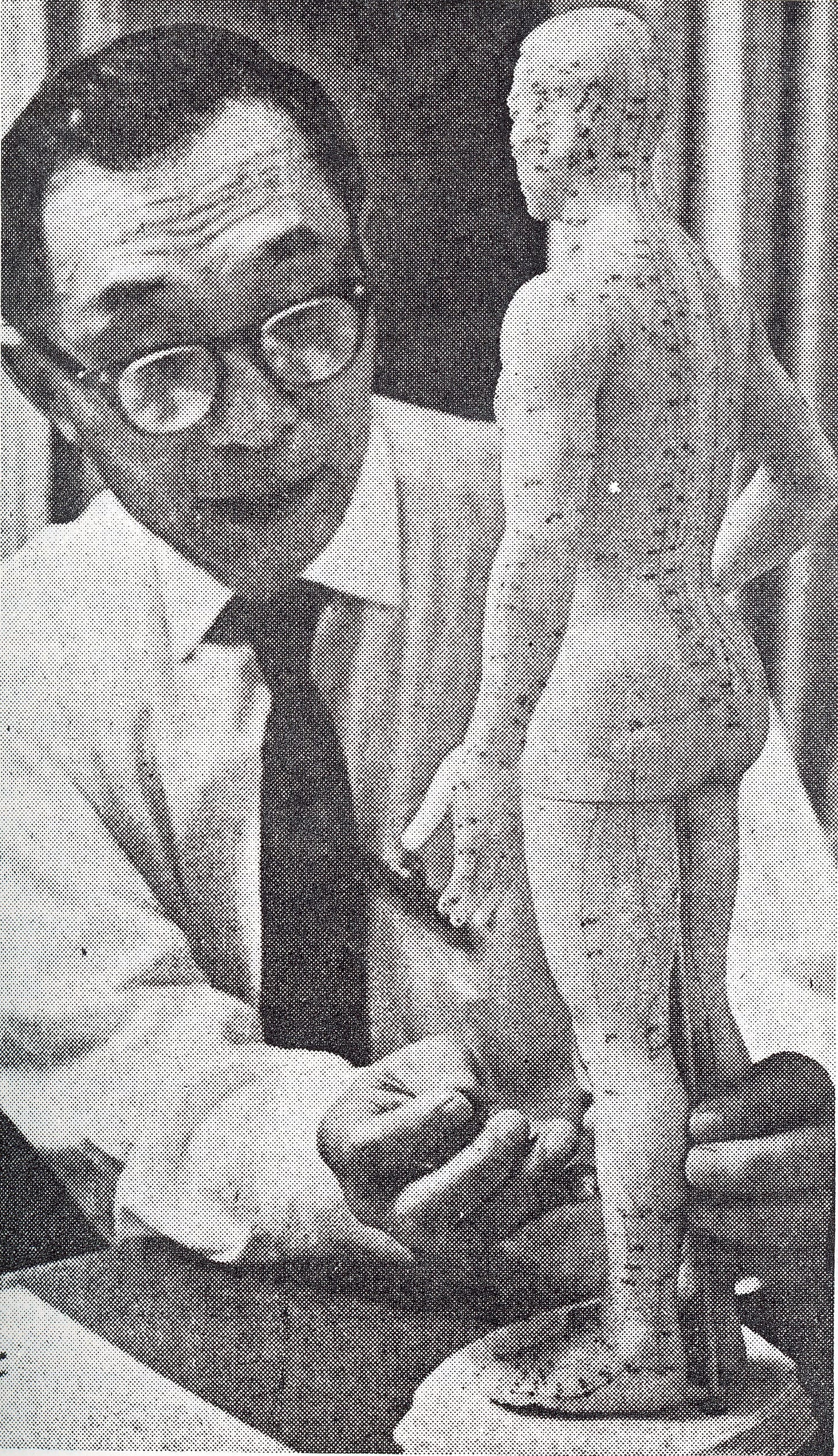

Born in 1911, Dr. Liang immigrated from China to San Diego, CA in 1949 where he worked as an engineer at Hughes Aircraft while quietly performing free community acupuncture, which had been his family tradition for 400 years.

In 1972, a group of White psychology grad students from UCLA–who had only just discovered acupuncture a couple years before–positioned themselves as the field's experts, named themselves the "National Acupuncture Association," and used their political clout to pass the US's first acupuncture law, AB1500, which granted themselves the ONLY legal licensure in CA–suddenly outlawing anyone else practicing, precipitating the arrest of 64 Asian practitioners, including the Bay Area’s Miriam Lee and even the UCLA cohort’s own teacher, Dr. Ju Gim Shek.

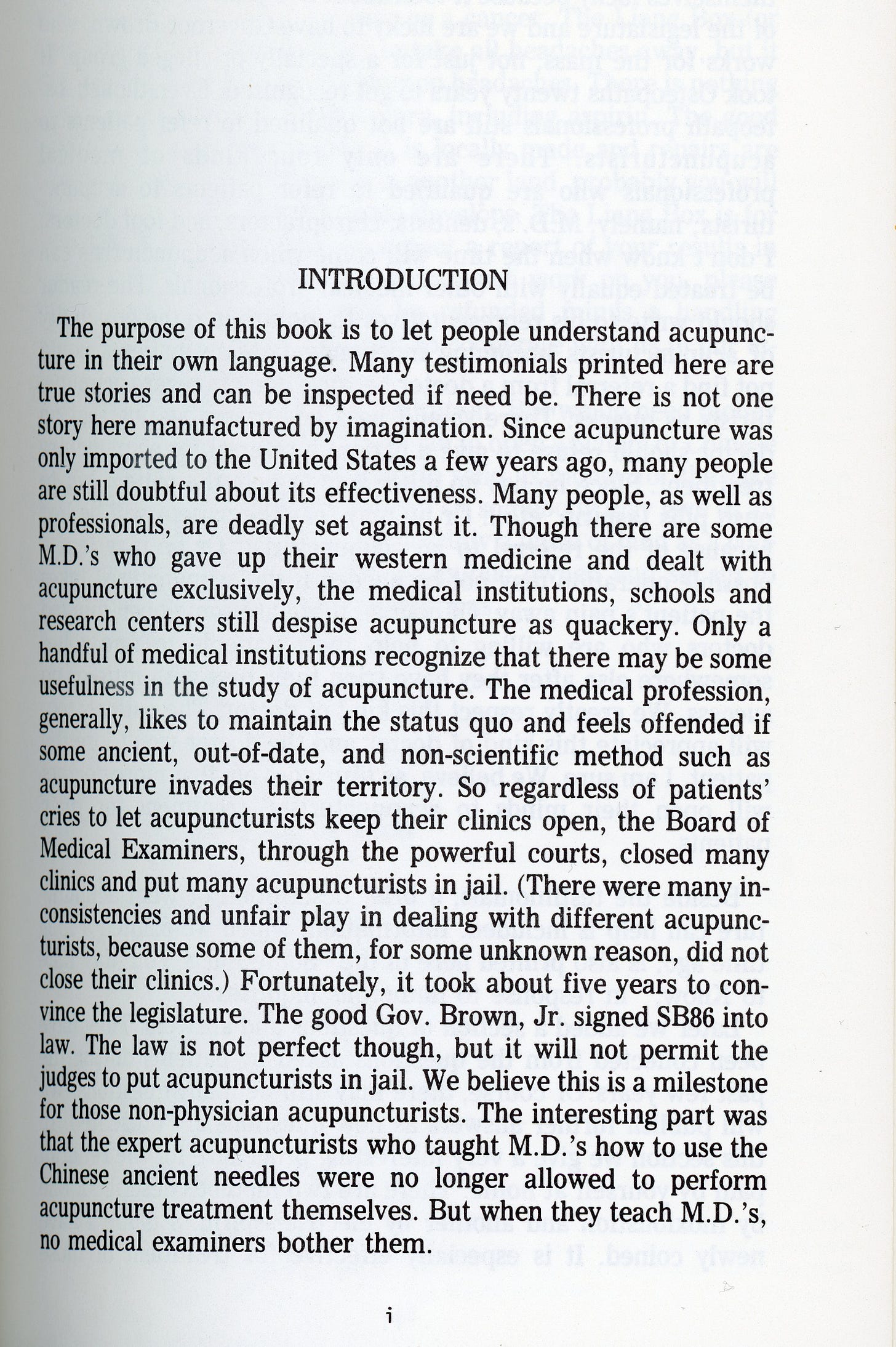

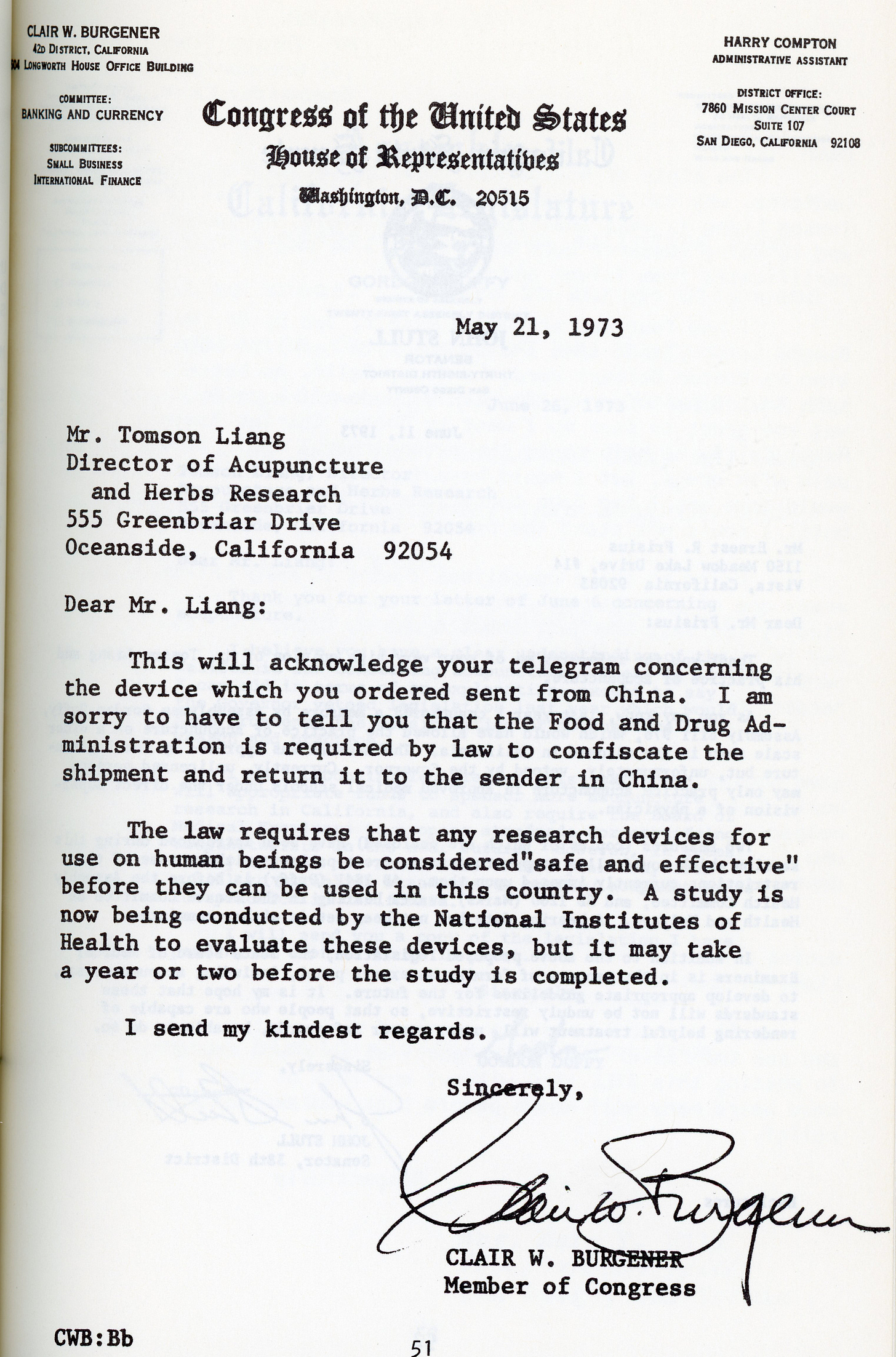

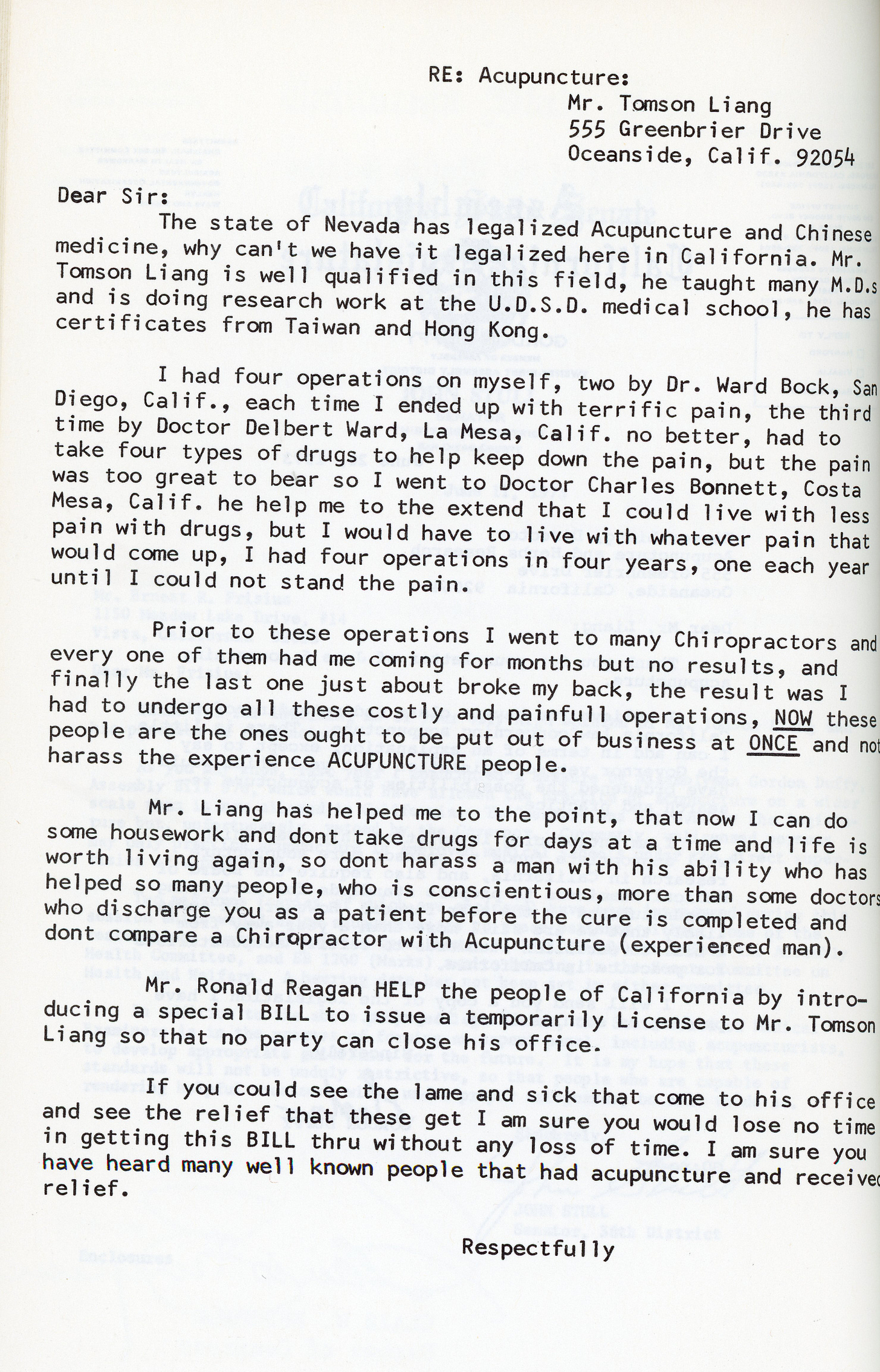

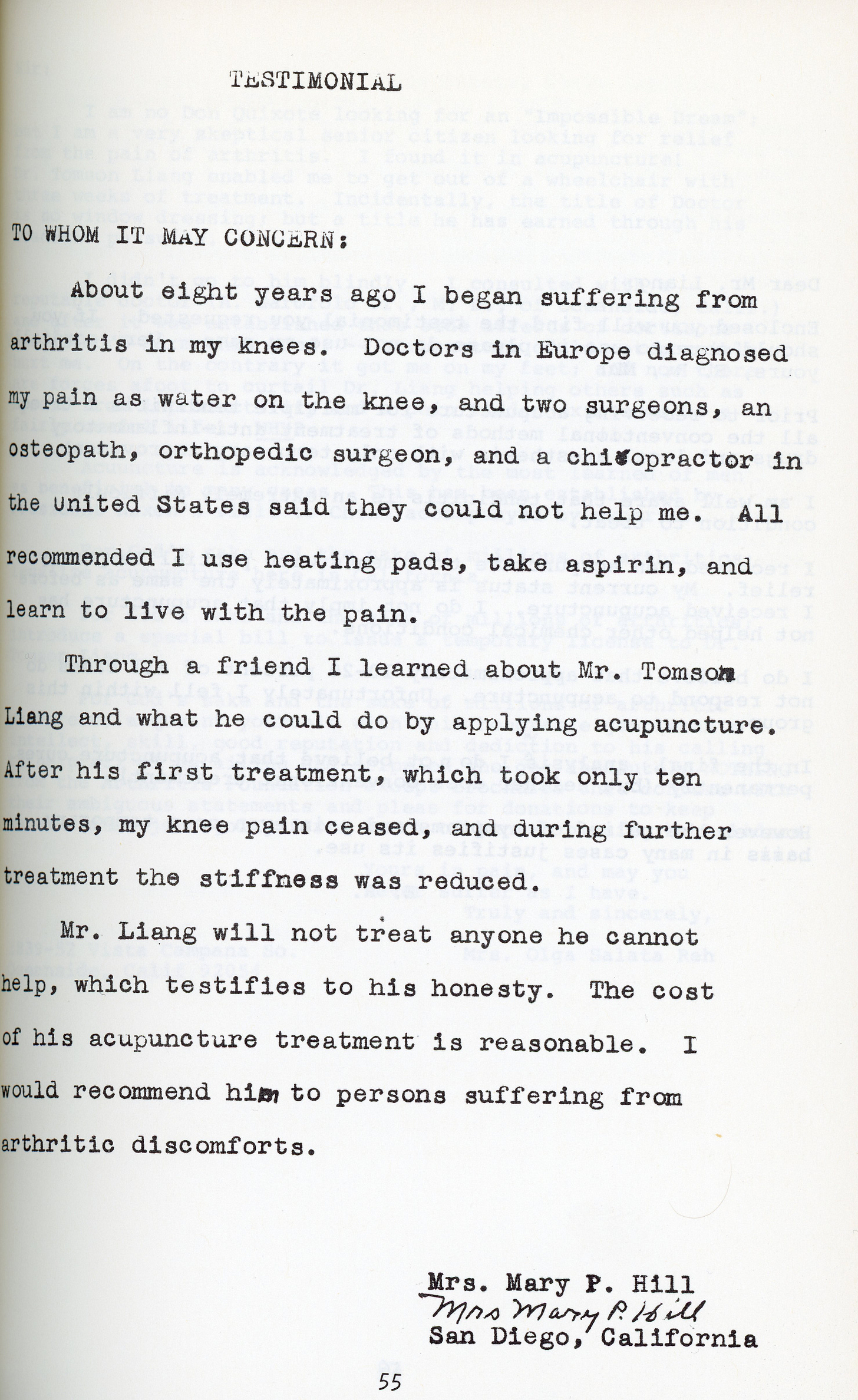

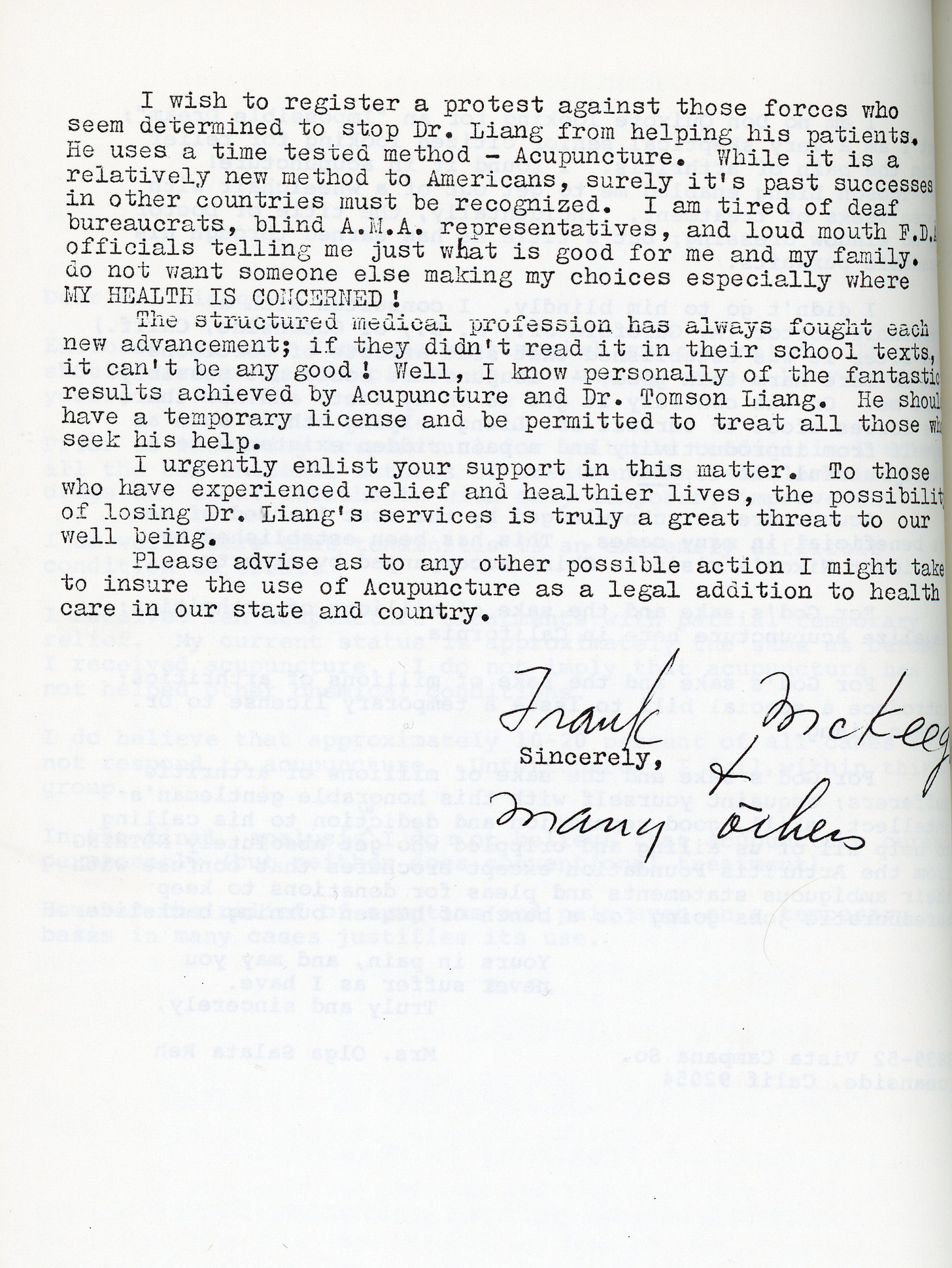

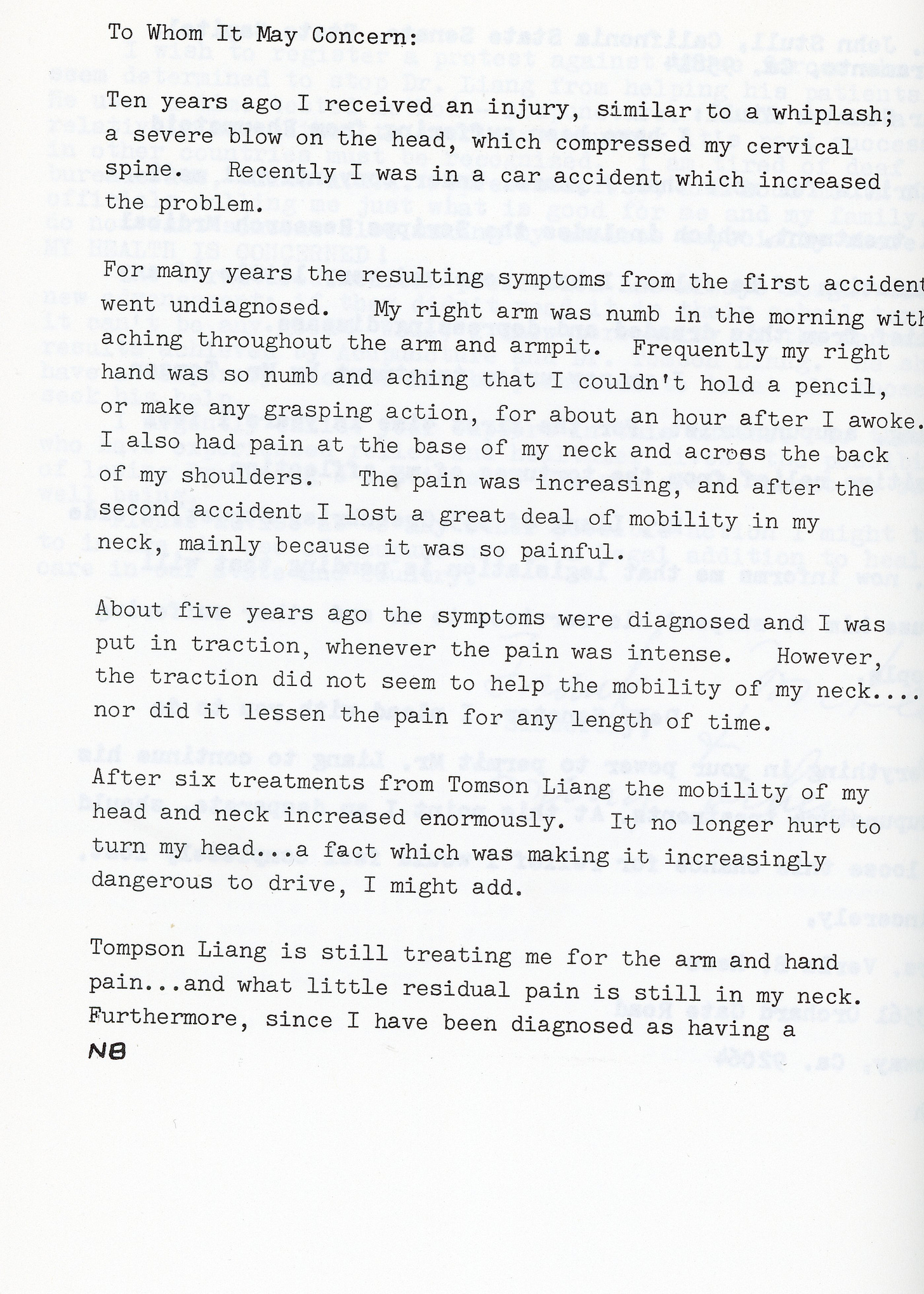

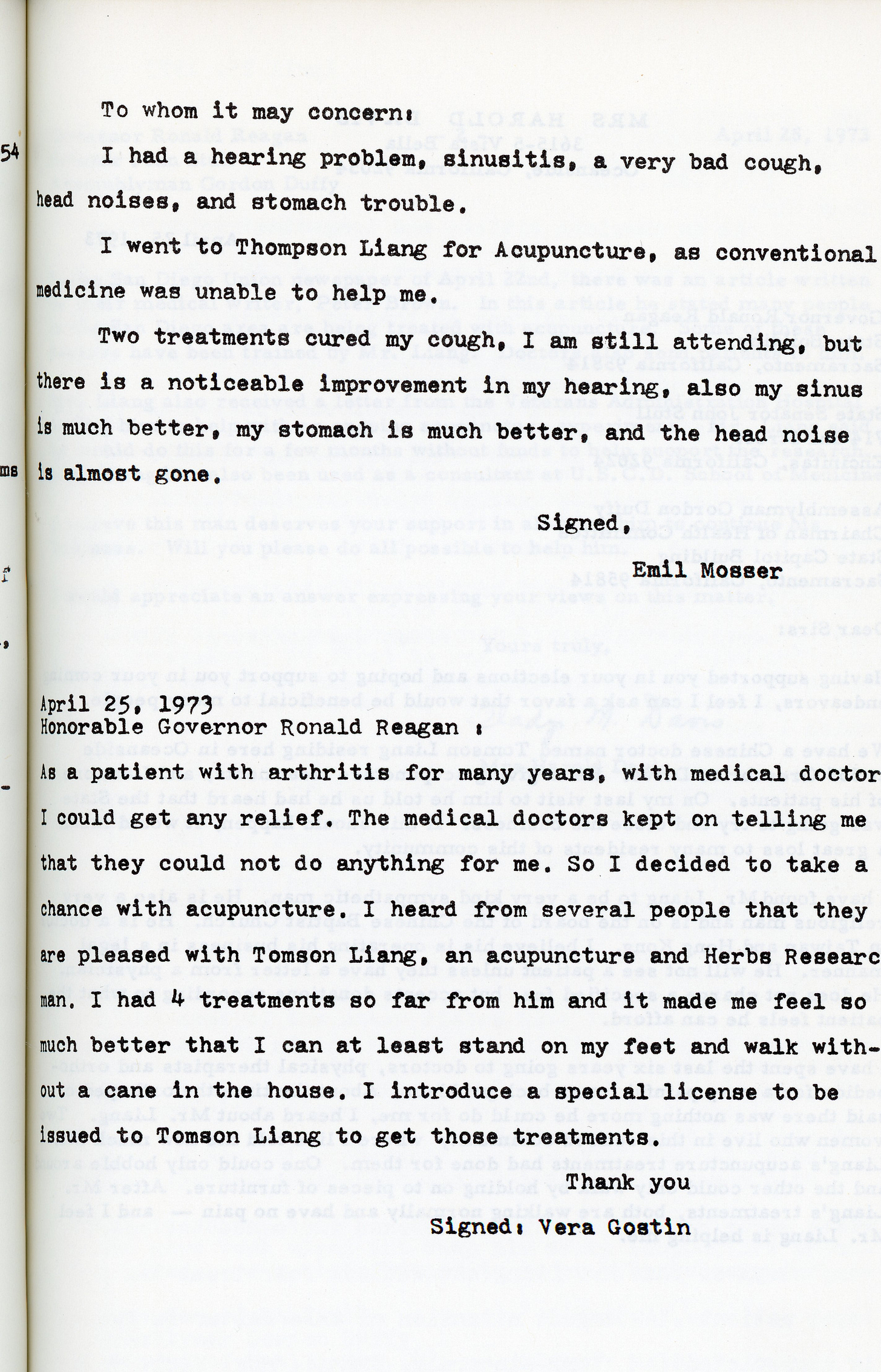

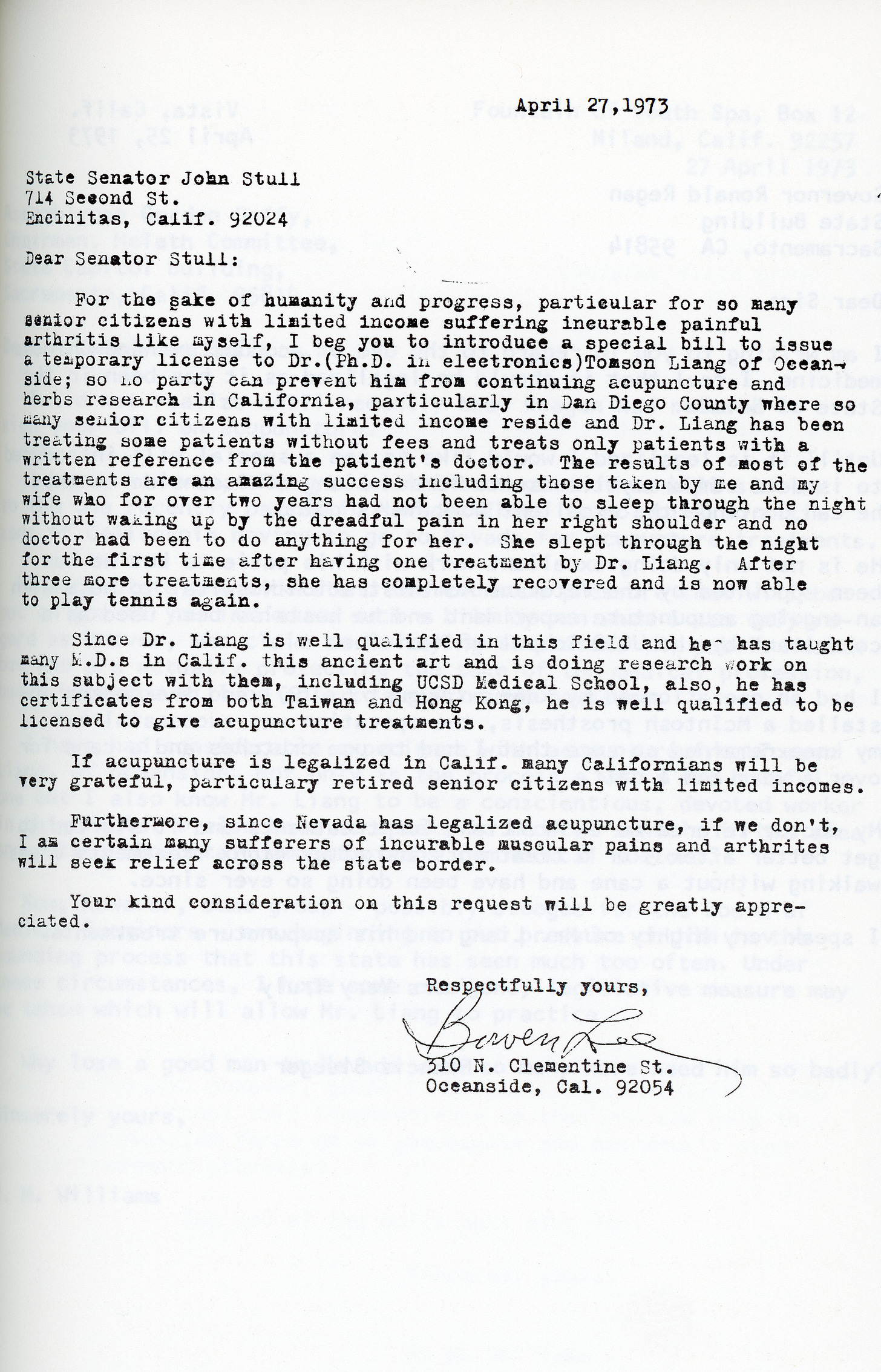

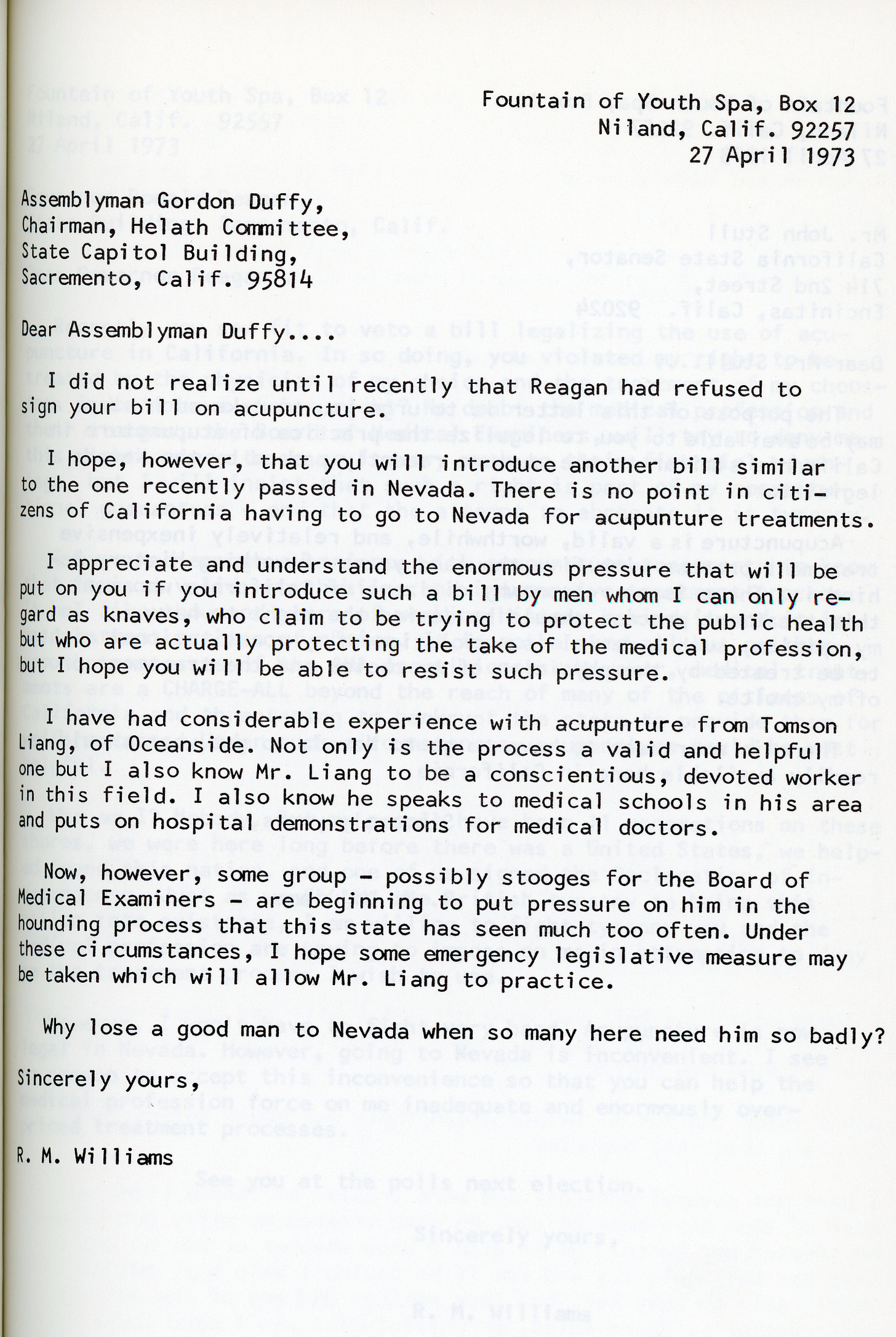

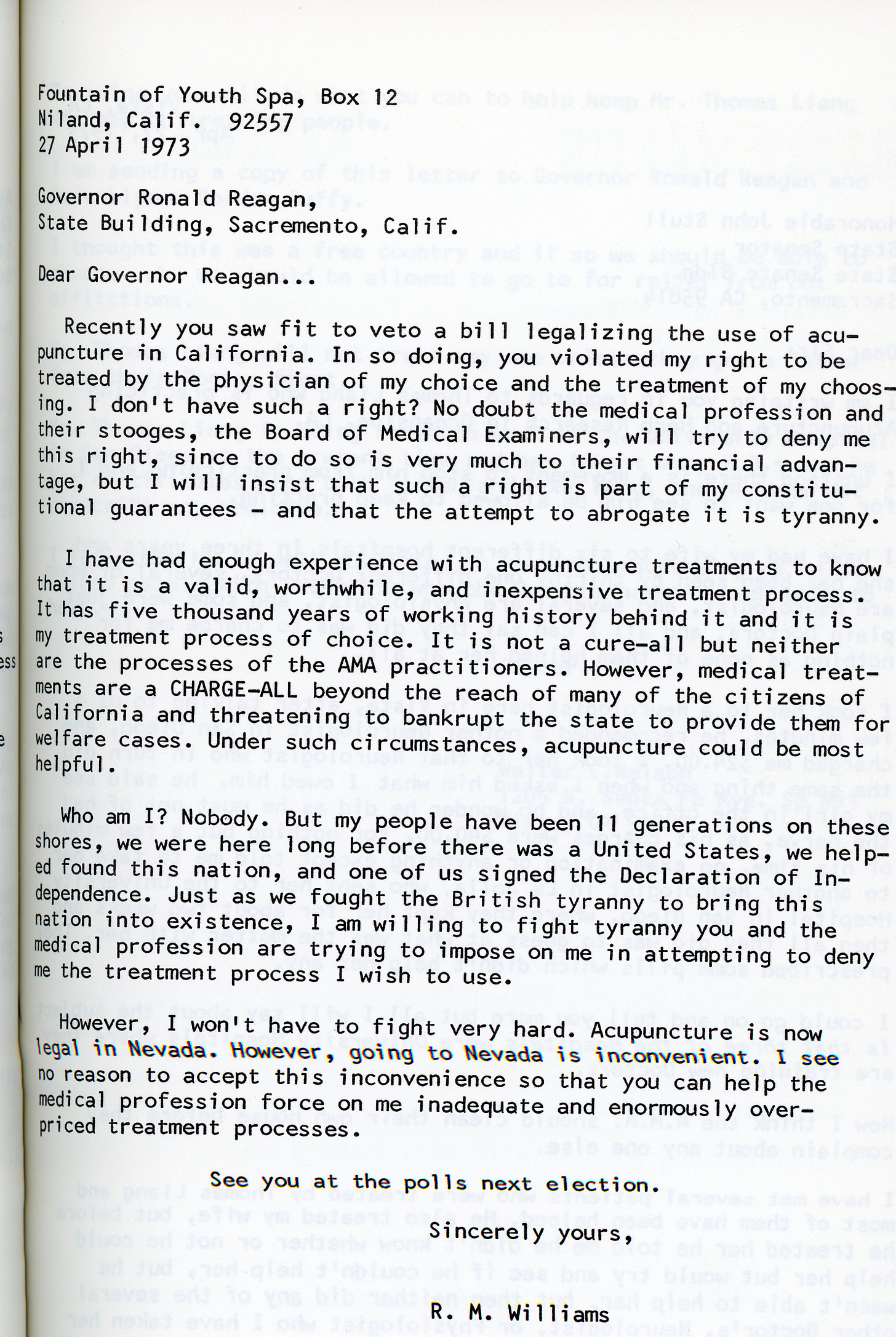

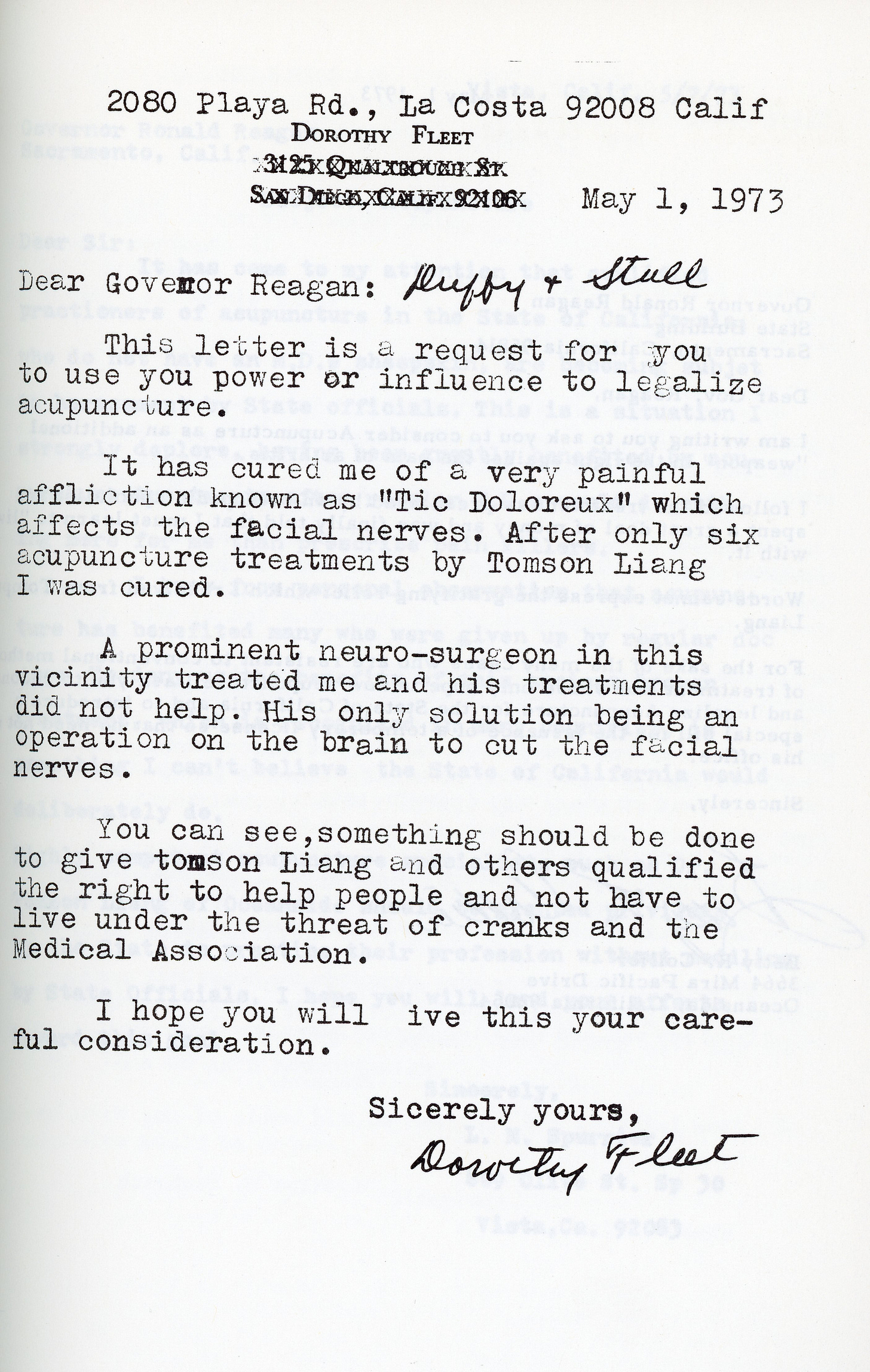

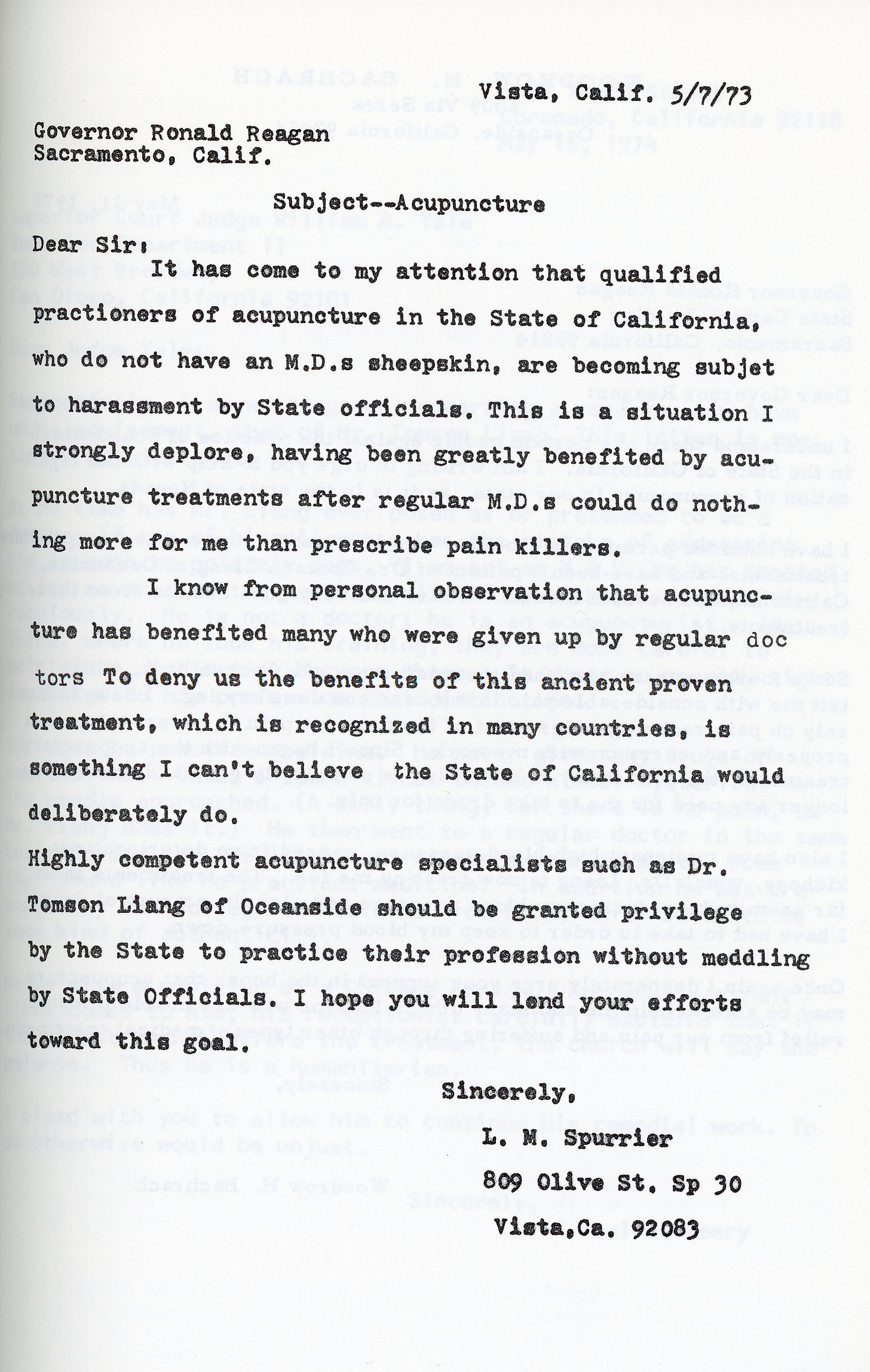

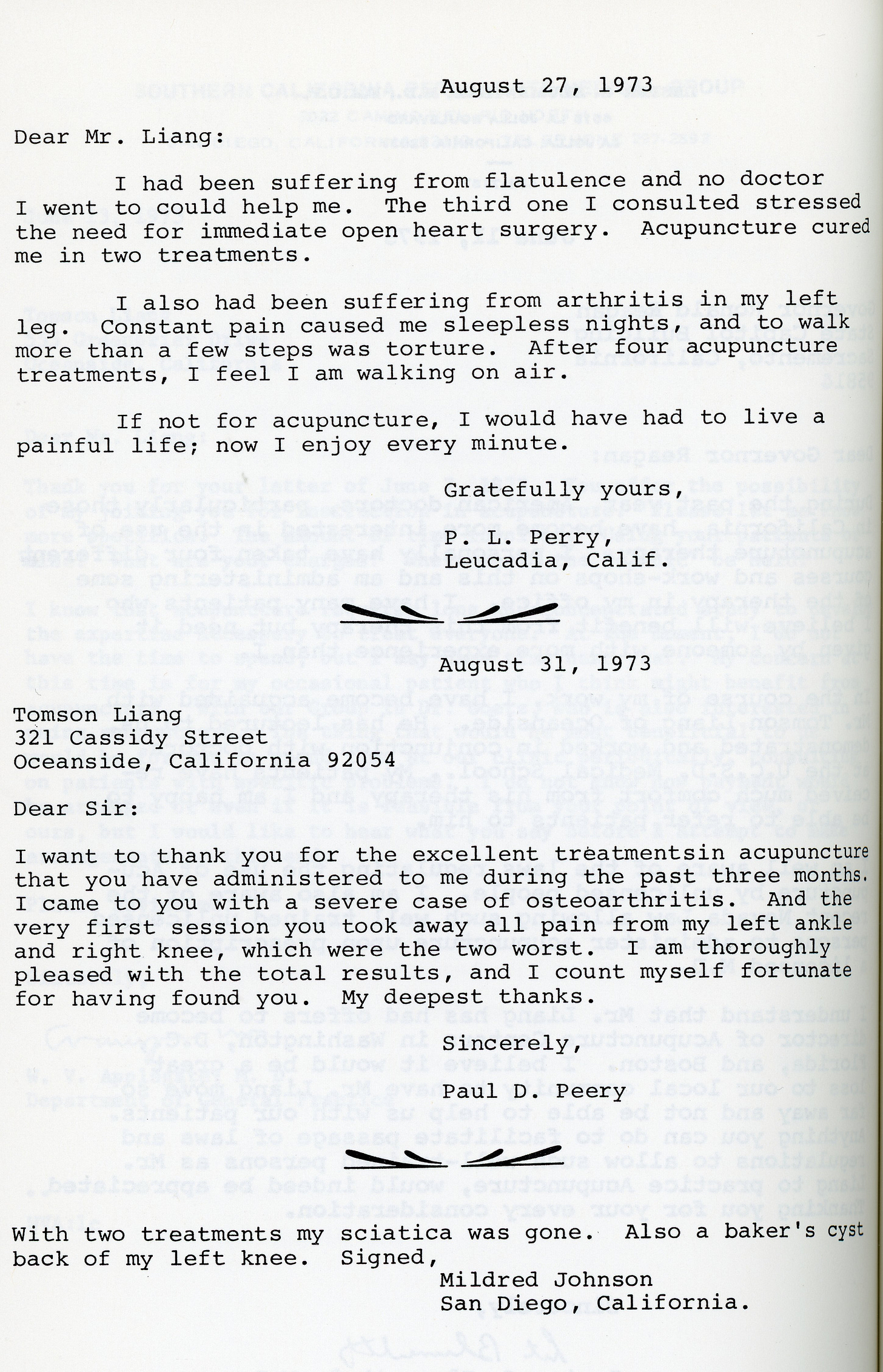

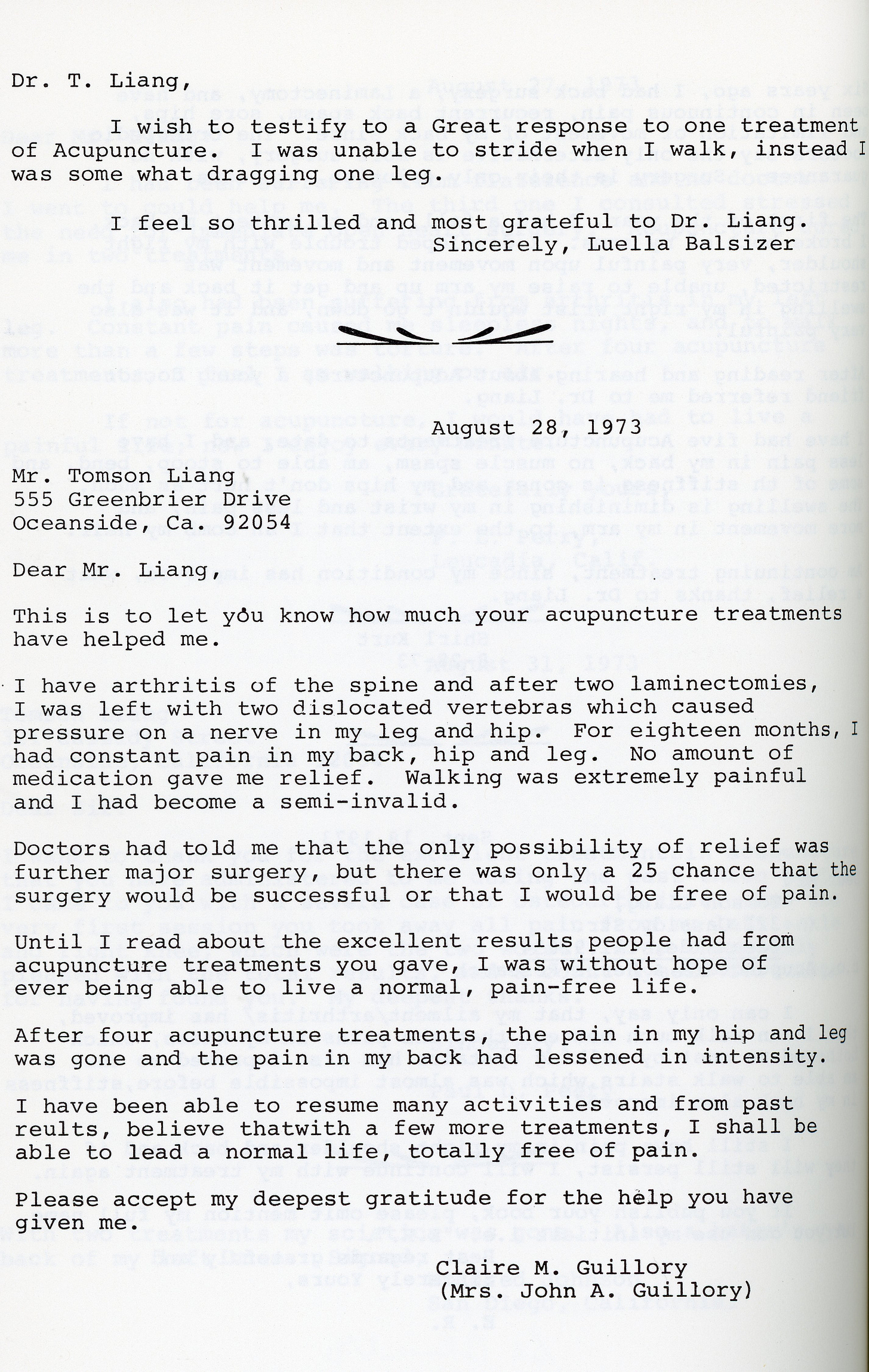

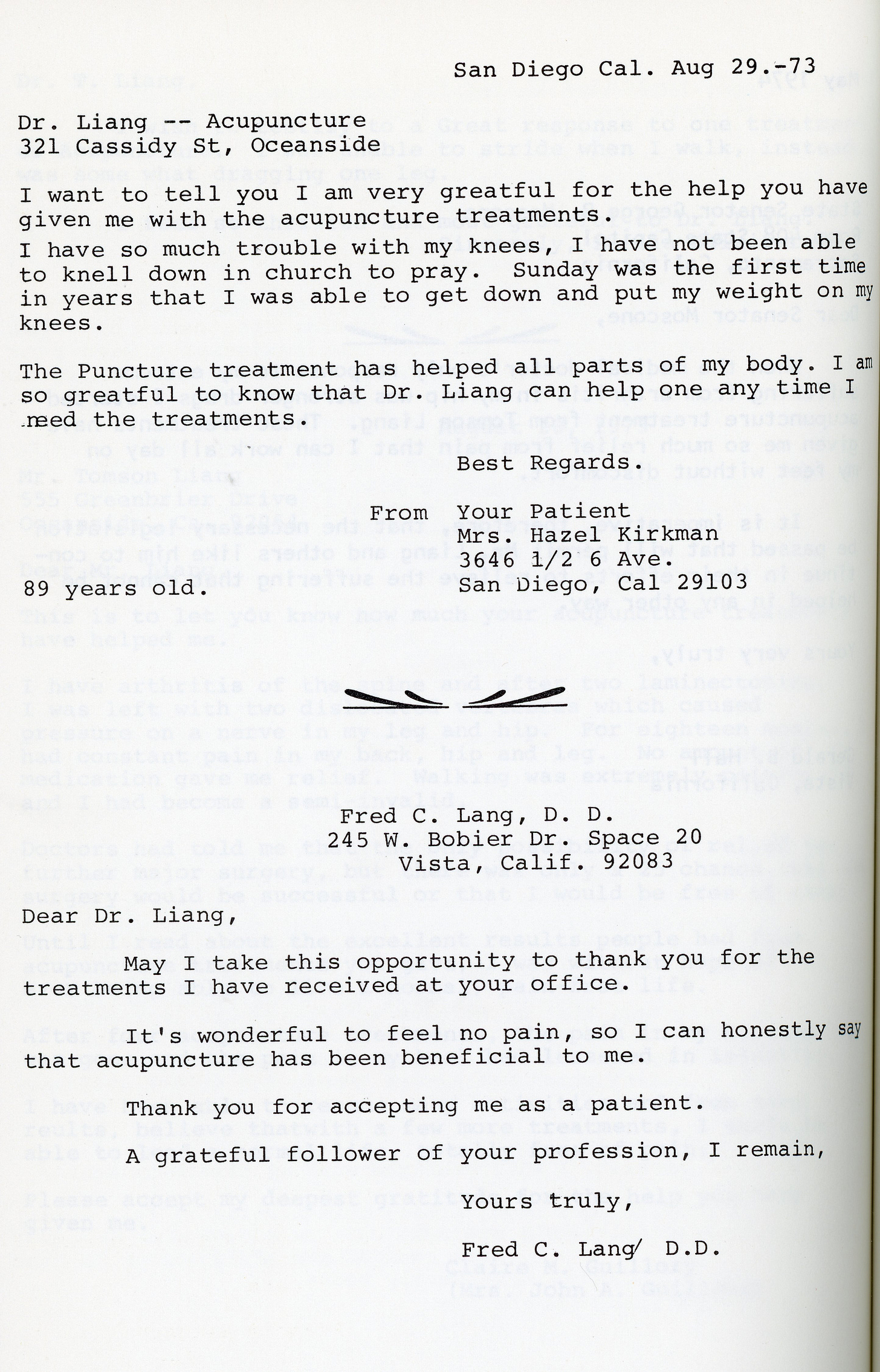

The book is a monumental compendium of Liang's unremitting struggle with the state of California to be professionally recognized and have his business reinstated, including his newspaper clippings, the lengthy correspondence between him and various politicians, and dozens of letters his supportive patients sent to then-Governor Ronald Reagan, who ignored the protests and refused to change the laws or free the jailed practitioners.

In one particularly persuasive letter, Dr. Liang addresses the contradiction head-on: "I taught many M.D.s to use needles; [but] because I am an unlicensed person, I should not use needles but only in an approved medical school under the direct supervision of an M.D. who knows nothing about acupuncture or even under a student which I taught to supervise his teacher. Does this make sense?"

The laws ultimately changed in 1975 only when Reagan left office to pursue national politics and Jerry Brown was elected governor; he signed SB86 which corrected AB1500 and paved the way for the licenses we have now. However, it was still the UCLA cohort who was tasked with creating both the curriculum required to obtain those licenses, and schools that would fulfill the curriculum.

That Dr Liang, whose parents and grandparents had been acupuncturists, was made to so-exhaustively defend his legitimacy for years to the White doctors whom he personally trained and politicians who literally knew nothing about the tradition is the shameful racism that is at the center of our profession, even now.

The book serves as a chilling reminder of the complicated relationship between White practitioners (which now make up roughly 75% of the profession) and the heritage of the medicine; and that our licensing bodies and the schools that service them–largely created by Boomer men (yes, I said it)–are not benevolently apolitical, egalitarian or above reproach, and are still regurgitating the gate-keeping of these various modalities, across so many fields but particularly in “wellness spaces.”

I like to think that perhaps they were well-intentioned and naively unaware of how colonization worked, but still they used their influence, wealth and understanding of American economic and political systems to monetize and legislate trades and cultures they really had no right to. And, worse, seemed unsympathetic and unfazed when that ownership damaged and criminalized those with legitimate claim.

As a Caucasian practitioner, I have to see myself in this lineage, even as I know better. I try to be mindful when I occupy space in “Chinese Medicine” dialogue online or in the press: how might I be affecting my Asian and Asian-American colleagues? And more insidiously–as my colleague Dr. Emily Siy once asked me to consider–how do I actually benefit from the absence or erasure of Asian people from the dialogue?

These are tough questions to confront but we must because we do not get to claim outright ownership of the knowledge, technique and history of these heterogeneous medicines simply because we bought into the professional legitimization created in the 1970s by people who manufactured their own "deed" for the usage of needles.

Or because we paid exorbitant tuition to private schools who work for the same institutional bureaucracies and are increasingly failing to meet the standards for gainful employment.

Particularly on the heels of the death of Dr. Mutulu Shakur–whose work with the Black Panthers and Young Lords to bring acupuncture to the states fought against the professionalization and credentialing that criminalized Dr. Liang–I hope we all take some time to reflect on how our work may be affecting our Asian and Asian American colleagues, many of whom will never sit for the boards, and remember that Dr. Liang's frustration, rage and grief is dyed in the ink in the licenses hung in all our offices.

-Russell Brown